By Robert Julian Stone

I have carried this in my head for almost half a century. On August 18, 2019, I broke my silence by sending a letter to the Acting Dean of the University of Michigan School of Literature, Science, and the Arts, and to the head of the University’s Student Health Service. It was time. But I was not prepared for where the letter would lead, or the new revelations that have shaken me, disturbed me, and continue to haunt me.

This is the letter.

***

August 18, 2019

Dr. Robert Ernst and Acting Dean Elizabeth Cole,

I am reaching out to you with this letter in hopes you will do everything within your power to make sure something like this never happens again at Michigan.

Anderson’s Boys

My Michigan #MeToo Moment, 1971

Some things you never forget. I was 20, an undergraduate in the school of Literature, Science, and the Arts, and a young gay man just coming to terms with his sexuality. Ann Arbor was a kind and tolerant place for those of us who did not conform to the gender-normative standards of the era. But there were times when medical issues could “out” us and leave us vulnerable.

Dr. Anderson was the head of the University of Michigan Student Health Service when I was an undergraduate and graduate student there. I saw him several times in December 1970 because of the recurrence of a hydrocele – an acutely painful testicular swelling. I was sent to his office, I believe, because I dropped in a dead faint onto the floor of the health service while I was standing in line to check-in to see a physician. The health service rotated students to whatever physician was available when you arrived. I believe they sent me to the head of the health service because my situation was clearly acute. Dr. Anderson prescribed medications which successfully addressed the problem.

But in June of 1971, I was told by a sexual partner that he had a sexually transmitted disease and he recommended I see a physician. This was a new experience for me and I didn’t know what to do. I was home for the summer, working a production line in a Detroit auto factory to put myself through school. I couldn’t see my family physician and the factory didn’t have one available for anything other than a work injury. So I reached out to a few gay male friends in Ann Arbor who were also Michigan students. One of them told me, “Go see Dr. Anderson, he’ll take care of you.” Seeing a physician of choice at the health service was rarely possible. Dr. Anderson was the Director of the university’s health service, and I couldn’t just name-request him. My friend continued, “It won’t be a problem, he takes care of all the gay guys on campus. And he doesn’t make those awkward referrals to the Department of Public Health. Just call his office and tell them I sent you.”

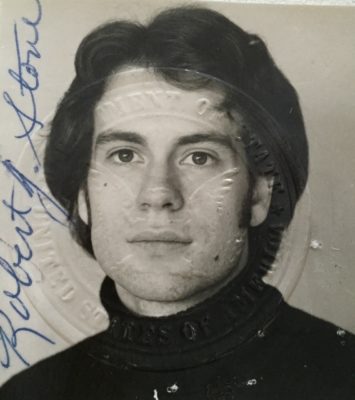

Robert Julian Stone, 1971.

I doubted my friend, but I didn’t know where else to turn. So I placed the call. I was somewhat astonished when I was given an appointment with Dr. Anderson two days later, on June 30, 1971. It was summer and I had to drive from Detroit to Ann Arbor to keep the appointment. Throughout my one-hour drive, I remained nervous and uncomfortable with my situation. I had never been exposed to a venereal disease, and I had only recently begun having sex with men.

I walked through the doors of the health service and paid the appointment fee. Then I headed for Dr. Anderson’s suite which was located prominently in the front of the building, not far from the main entrance. I identified myself to his receptionist and waited to be called. Soon Dr. Anderson emerged from his office and motioned me in.

Dr. Anderson was a short, rotund little man with brown hair, wearing a white lab coat over his street clothes. I guessed him to be about 40 years old. I don’t think he had any memory of me from the appointment I had six months earlier. After all, Michigan was, and still is, a big school. I glanced around the office as I sat down at his desk, noticing for the first time how spacious and well-appointed it was – much better than the offices of other physicians I had consulted for routine health matters. I sat in the chair in front of his desk, as he sat down opposite me. I will never forget the framed picture on the credenza behind him, showing the smiling faces of several young children and a woman I assumed to be his wife. The large window behind his desk opened onto Fletcher St. and sun streamed through Venetian blinds as I haltingly explained the information I received from my sexual partner. Dr. Anderson listened, then got up from his chair saying, “Let’s go into the exam room.”

He led me into a large adjacent examination room and asked me to take a seat in the room’s only chair. Anderson then launched into a dissertation about the symptoms of venereal disease (none of which I had) and what to look for. Nothing he said was new to me; I was naive, not stupid. I responded, “Thanks, this is stuff I know.” Then his presentation took an awkward and unexpected turn. He inquired, “Do you know how to pull back your foreskin and look for deposits or discharges?”

“I’m circumcised,” I replied, “so that’s not an issue.”

Then, without warning or hesitation, Anderson opened his lab coat and began to remove his belt and unzip his trousers. “Here,” he volunteered, “let me show you.” He proceeded to pull down his pants and boxers, jump onto the exam table, and begin the digital manipulation of his small, uncircumcised penis. He continued talking, offering some quasi-medical accompaniment for his masturbation. Anderson insisted I come over to the exam table. I stood up, walked over, and he placed my hand on his erect penis and asked me to pull back the foreskin. I complied, and then he placed his hand on top of mine and began moving it up and down on his erection. At this point, I knew exactly what this was; it was not educational. But I had not yet received the medical examination I needed. I had to get this over as quickly as possible, but I was not going to allow this to continue without the doctor’s acknowledgment of what was really going on.

So I asked Dr. Anderson, “Do you want to have an orgasm?”

He replied, “Yes.”

And so the doctor got the hand-job he was seeking. Afterward, he quickly stood up, cleaned himself off, and did a cursory exam of his patient. He took a slide off the tip of my penis (despite the fact that there was no discharge) and he drew blood. The tests would all come back “negative.”

When I left the office, I was horrified and dazed. How could such a thing happen to me, or anyone, at the school I loved? I was not traumatized, just disgusted. Before leaving Ann Arbor, I visited my friend who made the referral to Dr. Anderson, to tell him what happened. “Why didn’t you warn me?” I protested. My friend just shrugged his shoulders and looked away. Evidently this was the price all Dr. Anderson’s gay male patients paid for his services and confidentiality. Everyone simply endured it. It was 1971; homosexuality was still classified as a mental illness by the American Psychiatric Association. We were “beggars, not choosers” and we just had to “man-up” and take it.

I saw Anderson for a follow-up, and the exam was strictly business, without a sexual component. After this, I guess you could say I became one of Anderson’s boys. He would see me whenever I needed, and all the subsequent exams were strictly professional.

Almost half a century has passed, and I have often thought about it this experience. I wondered if it happened multiple times to some of Anderson’s gay patients, or if there was only one introductory “lesson” for each of us. I will never know because we didn’t talk about these things in those days. I moved to San Francisco after finishing graduate school at Michigan. And most the gay men I knew and loved in that magical city did not live to see old age, as I have. I’m a lucky man, now married to a retired physician. The irony of this is not lost on me.

In 1993, I requested my medical records from the University. They were sent to me in the mail, and there on the dark, poorly photocopied record was Dr. Anderson’s annotations for my visit of June 30, 1971. It showed “slide neg, VDRL” and the cryptic annotation “V.D. Survey” which I now assume was the doctor’s code for the special treatment he reserved for his gay male patients.

I am the author of four books, under my pen name Robert Julian. And I briefly toyed with including a chapter on this experience in one of them. But frankly, I couldn’t bring myself to relive it. Only recently have I been able to sit down and write it out. I hold no ill-will toward the University or Dr. Anderson. I imagine the doctor’s closeted life was not an easy one. But when abuse survivors come forward to report long-suppressed instances of sexual abuse, I don’t doubt them. Once you have had your own #MeToo moment, it changes you. And you never forget.

Robert Julian Stone

B.A. ’72

M.A. ‘73

***

I felt a palpable sense of relief as soon as I released the letter. It was a turning point for me. I received appropriate responses from the addressees, with Acting Dean Cole explicitly stating in her response, “I believe you.” Cole also said, “I will forward your message to the University of Michigan Police Department and our Office of Institutional Equity.”

I was surprised Cole would make a referral, since I assumed (correctly, as it turned out) that Dr. Anderson was dead. That assumption was part of the reason I waited so long to step forward. If my abuser was dead, then what would be the point? A few days later, I got the phone call.

“Hello?” the man’s voice said. “I’m trying to reach Robert Julian Stone.”

Detective Mark West of the University Police Department introduced himself to me, explaining that he was calling about the letter. He spoke calmly in a slow, measured tone. I quickly identified the Michigan accent I remember from my childhood. Detective West is in charge of the investigation into Dr. Robert E. Anderson, who died in November 2008.

“I want you to know that you are not the only victim of Dr. Anderson. There were many others, and not all of the men were gay.”

“Thank you,” I exclaimed, with conviction and relief, “thank you for telling me that. I knew there had to be others, but I didn’t know if anyone had spoken out.”

Detective West acknowledged that the #MeToo movement has brought out many of Dr. Anderson’s accusers; additional victims are being reported to West on a regular basis. It appears the University realized at some point that there was a problem with Anderson, but instead of taking disciplinary action, they transferred him out of the Health Service and made him the team physician for the Michigan football team. Which, in essence, was putting the fox in charge of the chicken coop. Now former team members are stepping up to report their treatment at Anderson’s hands.

As team physician, he allegedly performed regular and unnecessary prostate exams of the players. The number of instances has not yet been determined. As West answered my questions about the investigation, I began to get a sickening feeling that lingered after the phone call ended. West will be developing this case over time, as new accusers come forward. All the assault allegations against Dr. Anderson are being combined into one case report that will be forwarded to the Ann Arbor Police Department upon completion. West said he would send me a redacted version of the case report once it is complete, omitting only the names of the accusers. He shared with me the case number.

Why didn’t I speak up sooner? If I had stepped up, could I have prevented this sort of thing from continuing for decades? I feel more than a little guilt. In my August letter, I labeled Anderson “a closeted gay man,” expressing some compassion for an individual living through that experience. I now realize this was not “a closeted gay man.” This was a sexual predator, routinely using the physician’s exam room as a venue for assault. The horror of this is still sinking in. That room still lives in my head after all these years. Michigan State had its Larry Nassar, and Michigan had my doctor: Robert E. Anderson.

I’m still processing all this. I’m always following trails of “what if” through a shape-shifting landscape of the past. In committing this story to print, at this moment in time, I feel vulnerable. It is still raw. I am still angry, angry for that vulnerable young man I once was. A man who expected “First, do no harm” to be the golden rule of medicine. I still ask myself, “How could anyone do this sort of thing?” I have no answer, but these thoughts won’t be going away soon.

***

Robert Julian Stone is an author and journalist living in Palm Springs, CA. His Facebook author page is https://www.facebook.com/RobertJulianAuthor/.